ComEd’s $650 million power play

As documented in our December, 2020 report, Guaranteed Profits, Broken Promises, ComEd built an unparalleled political influence operation to pass the 2011 Energy Infrastructure Modernization Act (EIMA), the law creating automatic “formula” rate hikes. Once built, ComEd continued to use its influence operation to win further windfalls for ComEd and Exelon. One of the best examples was when it returned to the Illinois General Assembly for more profits through a 2013 EIMA trailer bill. In our report, we calculated that this power play resulted in at least $400 million in additional profits for ComEd since the trailer bill passed in 2013, all paid for by ComEd’s customers. With new and additional analysis, we are updating our calculation to over $650 million.

As documented in our December, 2020 report, Guaranteed Profits, Broken Promises, ComEd built an unparalleled political influence operation to pass the 2011 Energy Infrastructure Modernization Act (EIMA), the law creating automatic “formula” rate hikes. Once built, ComEd continued to use its influence operation to win further windfalls for ComEd and Exelon.1 One of the best examples was when it returned to the Illinois General Assembly for more profits through a 2013 EIMA trailer bill.2

In our report, we calculated that this power play resulted in at least $400 million in additional profits for ComEd since the trailer bill passed in 2013, all paid for by ComEd’s customers. With new and additional analysis, we are updating our calculation to over $650 million.

A fight over formula rate accounting

ComEd returned to the Illinois General Assembly in 2013 to overrule decisions made by the Illinois Commerce Commission and its accounting experts in its implementation of EIMA.

This multi-year standoff began when ComEd refused to initiate the investments that the legislation it championed obliged it to do,3 on its proposed and approved schedule,4 because it disagreed with three Commission accounting decisions which did not add some of the company’s future profits ComEd felt it was owed from the law.5

During this back and forth between the Commission and the company, the Commission “asked for specific proof regarding […] the Company’s finances.”6 Rather than providing such proof, ComEd engaged in extraordinary tactics, including not complying with a Commission order,7 and manipulating the regulatory process in a manner that left the Commission with no good options.8 Two proceedings9 include detailed commentary from the Commission on the company’s failings which Commissioners unanimously criticized, for example calling ComEd’s conduct “disappointing,”10 and “deficient.”11

ComEd first attempted to change the Commission’s course through House Resolution 1157 & Senate Resolution 821, which detailed the three accounting disagreements, expressing “serious concerns” regarding the Commission’s decisions, and urged the Commission to “strongly consider reversing its conclusions with respect to each of these 3 issues.”12 Under pressure, the Commission relented on one of three accounting disputes upon rehearing; it did so begrudgingly, by refusing to call the practice “sound policy” and warning it was “not the approach to pensions that the Commission would take on its own.”13

Not satisfied with this outcome, which could have been undone by the Commission, ComEd returned again to the Illinois General Assembly to pass a trailer bill to overrule the Commission’s judgement on the three accounting decisions, granting ComEd its desired additional profits.14

At the time, ComEd argued these additional profits were necessary to begin its EIMA-obligated investments,15 going so far as to not begin its investments as mandated by the law it championed. With the benefit of hindsight, as we document in our report, this was clearly not the case,16 as formula rates have provided the financial resources necessary to make the EIMA-obligated investments several times over.

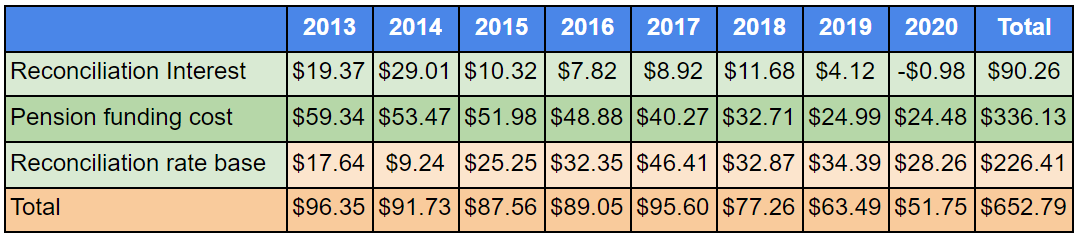

Even though the law’s advantages for ComEd were more than enough, the company still decided to force customers to pay more. Due to the Illinois General Assembly’s 2013 intervention on the three contentious topics, ComEd earned an additional $653 million between 2013-2020.17

The disputed accounting

The disputed accounting is complicated, and difficult to understand without knowledge of how formula ratemaking works. Here is an attempt to explain in relatively simple terms.

These calculations should be considered accurate but still “ballpark” estimates. The pension figure is relatively easy to calculate, as the amount is listed in each year’s update to the formula which sets ComEd’s rates. The other two calculations involve the highly complicated and interactive reconciliation, or “true-up,” process. On top of this, the analysis does not consider potential changes in ComEd’s behavior had the 2013 law not passed. That said, these numbers provide an instructive ballpark estimate of the additional profits ComEd has earned due to the 2013 law.

-

Reconciliation Interest

The annual formula rate process involves a two-tiered process using actual company expenses, as reported to state and federal regulators, to look both forward and backward one year.18

The forward-look would be recognizable to anyone familiar with a traditional rate-setting process, in that it utilizes estimates to modify the most current utility costs to set the authorized rates for the following year. The backward-look, or “reconciliation,” however, is critically different, as it uses the company’s actual expenses to calculate what revenue it should have collected and compares that with what the company actually collected.

If the company under-collected for the year, it is able to make those revenues up, with interest, through an adjustment to future customer bills. If it over-collected for the year, it similarly credits money back to its customers. This reconciliation process allows the company to annually “true-up,” eliminating the uncertainty purposefully embedded in the traditional rate setting process and in so doing changing the utility’s opportunity for profits into a guarantee.

There are two primary ways that an over- or under-collection could occur. One is the weather and associated customer consumption. In hotter years, air conditioning usage drives up overall consumption and utility revenues. In milder years, usage and revenues will be less. The second primary cause of over-or-under-collection is if the company spends more or less than it estimated. Formula rates are unique in addressing this form of over- or under-collection. For example, if the company estimated it would invest $100 in its grid but it actually spent $120, it would earn an extra $20, with interest, the following year.

As the Commission explained at the time, “in light of the increasing plant expenditures each year, the legislature arguably created a system under which under-recoveries by the utility will be the norm.”19 Given that under-collections would be the norm (and in hindsight, they have been), the level of interest accrued on the under-collected amount collected later from customers may significantly impact ComEd profits.

This interest level is the focus of the first accounting dispute. The Commission decided the interest level should be the same as ComEd pays for short term debt, as if ComEd had loaned the money to its customers for two years and was collecting the loan back along with an interest rate appropriate for such a short term loan.20 The short term interest rate has been, on average, around 1 percent over the time period in question, though it was lower at the time of this dispute. ComEd wanted the interest to be its overall Rate of Return, which has been, on average, around 7 percent over the time period in question.21

This difference has led to $90 million in additional ComEd profits.

-

Pension Funding Cost

In utility ratemaking, operating costs, like office supplies and staff salaries, are treated differently than investments, like in the poles, wires, and smart meters that deliver electricity to our homes and businesses. Utilities collect operating costs back from customers with no profit added; they collect investments back with an additional return, or profit.

Under formula rates, the Commission initially decided ComEd’s annual pension investments should only be treated like an investment if the pension fund had more cash than liabilities, that is, only if ComEd more than fully funded its pension fund.22 ComEd, however, argued that an investment return should be provided on all of its pensions, net of deferred tax benefits.23 ComEd argued that if “the General Assembly had intended the “pension asset” to only mean any value in excess of the overfunded amount in a pension fund, it would have written “pension assets net of total liabilities” into the statute, not “pension assets net of deferred tax benefits”. The Commission concluded that “when using the words “pension assets” in Section 16-108.5, the General Assembly most likely intended to refer to the amount that ComEd lists as a “pension asset” in its FERC Form 1 filing”. The Commission adopted that definition as the amount of the “pension asset” but stated that this” is likely not the approach to pensions that the Commission would take on its own.”24

The law allows ComEd the “pension asset net of deferred tax benefits” to earn a return at the same level ComEd pays for long-term debt, around 5 percent over the time period in question

This change has led to $336 million in additional ComEd profits.

-

Reconciliation rate base

As described above, the annual formula rate process involves a two-tiered process to set rates, including the forward-looking projected year, and an amount providing recovery of the actual cost of the prior year, the backward-looking reconciliation year. In rate setting, ratepayers provide recovery of a return, or profit, on the “rate base” which includes the company’s investments.

In the forward-looking process, the upcoming year’s rate base is estimated by adding the projected plant additions for the forward year to the prior year’s actual end-of-year rate base. So, in the 2018 rate case, the formula adds the anticipated 2018 plant additions to the total amount of the rate base at the end of 2017. Then, in this example in 2019, the formula will look back at the 2018 rate base, to see how the earlier estimate compares to what actually happened. Discrepancies between the two would impact what customers would pay in the following year, 2020. The third accounting dispute was over what amount the formula would use for the “2018 rate base reconciliation.”

The Commission decided to use the average value of the rate base over the course of the year.25 That is, in a hypothetical example, if the rate base increased from $10 billion to $11 billion over the course of 2018, it would use $10.5 billion as the 2018 rate base value for the purpose of the reconciliation process. ComEd wanted to use the year-end value, that is, in this hypothetical, $11 billion.26

The Commission reached its conclusion in part based on staff analysis, which explained:

Staff avers that use of a Year-End Rate Base calculates the reconciliation revenue requirement in a manner that assumes that plant in service at the end of the year was actually in service for the entire year, which, according to Staff, is clearly not the case. Staff argues that Year-End Rate Base is not accurate for purposes of calculating the reconciliation revenue requirement because it is a snap-shot of rate base on a single date; it is not representative of cost information for a calendar year.”27

The 2013 trailer forced the Commission to adopt a figure its staff deemed inaccurate.

This difference has led to $226 million in additional ComEd profits.

Customers have paid $650 million more as a result

Additional ComEd profits due to General Assembly intervention in millions28

These changes all directly add to ComEd’s profits and raise customer bills, while delivering no additional value to its customers.

- Changing the level of interest earned on what is at best a short-term loan does not make those investments any better

- Allowing ComEd to earn a profit on pension expenses does not change their pension obligations or reduce the future amounts that will be collected from ratepayers

- Changing the accounting for spending in their rate base does not make their investments better or make more investments.

Even without these additional profits, EIMA turned utility regulation on its head, using promises of what the EIMA investments would achieve to win itself guaranteed profits with less accountability. ComEd is on track to add three times as much to rate base as it said it needed formula rates for, automatically providing excess company profits through formula rates. These three accounting changes delivered even further, unnecessary profits for ComEd and its 99.985% shareholder, Exelon.

As such, this is a perfect example of how ComEd used its clout: overturning the conclusions of its regulation experts at the Illinois Commerce Commission and turning instead to the Illinois General Assembly for additional guaranteed profits, paid for by customers, while ensuring only minimal customer or public benefits in return.

Notes

1. Cahill, Joe, Exelon, ComEd discover the downside of successful lobbying, Crain’s Chicago Business, October 18, 2019.

2. Public Act 98-0015.

3. See 220 ILCS 108.5(b) for the requirement to begin investment, and 220 ILCS 108.5(l) for language added in the 2013 trailer bill stating that ComEd “shall be deemed to have been in full compliance with all requirements of subsection (b)” and that the Commission could not investigate ComEd’s compliance or penalize it for noncompliance.

4. ICC Docket No. 12-0298, Order on Rehearing, 31, 33.

5. Ibid, 17-19.

6. Ibid, 29-30

7. Ibid, 33.

8. Ibid, 25-26, 29, 31. “The Commission is stuck between the evidentiary problems resulting from ComEd’s legal theory and the result of ComEd’s refusal to comply with a Commission Order. ComEd’s tactics have left the Commission with a poor evidentiary record and no good options.” “ComEd specifically removed all mention of the impact of the Docket 11-0721 Order in an errata filed the day Staff and Intervenor Direct Testimony was due. […] The Company did not make a prima facie showing in its direct case of why the Commission’s June 22, 2012 Order should be changed. ComEd did not attempt to make this showing until its Rebuttal Testimony – to which no party had an opportunity to respond,” “The Commission, however, agrees with Staff’s assessment that: […] Likewise, any staffing issues that ComEd may have do not appear to be the cause of the delayed deployment schedule, but rather are a result of ComEd’s decision to delay deployment.”

9. ICC Docket No. 11-0271 on Final Order on Rehearing and ICC Docket No. 12-0298 Order on Rehearing.

10. ICC Bench Session Minutes, December 5, 2012,14-18. Chairman Scott said ”Having said that, there is one thing that I would like to say. The narrative surrounding this case has been pretty disappointing to me and it’s just a narrative because there has been more than that. I think the Judge did a very good job of laying out in the Order which we just passed. So I won’t hash it in detail, but we see things like testimony introduced and then asked to be pulled through an errata document which obviously is highly unusual to say the least saying that the testimony could have been misinterpreted and then telling us essentially that none of this is about the money and we can’t even consider the money in this case when the narrative outside of this room is that it’s all about the money in this case. And then we see the $100 million figure that we’ve seen outside of here come back into play in rebuttal testimony with, as the Order points out, very little to support that and that’s the same dollar figure we’ve heard for a long time which strangely didn’t change after we essentially put back in the pension asset, which in the reconciliation cases estimated to be about $70 million and that number hasn’t changed. That is much larger than the number which is confidentially kept in the testimony in this case, which is also troubling and as the Order I think really points out a lot of this …”

11. ICC Special Open Meeting Minutes, June 22, 2012, 20-22.

12. 97th General Assembly, House Resolution 1157, 5.

13. ICC Docket 11-0721 Order on Rehearing, page 24

14. The law also specifically shielded the company from the penalties EIMA imposed on ComEd for its noncompliance with investment obligations. Public Act 98-0015: in part, 220 ILCS 5/16-108.5(k) and (l): “(k) The changes made in subsections (c) and (d) of this Section by Public Act 98-15 are intended to be a restatement and clarification of existing law, and intended to give binding effect to the provisions of House Resolution 1157 adopted by the House of Representatives of the 97th General Assembly and Senate Resolution 821 adopted by the Senate of the 97th General Assembly that are reflected in paragraph (3) of this subsection. In addition, Public Act 98-15 preempts and supersedes any final Commission orders entered in Docket Nos. 11-0721, 12-0001, 12-0293, and 12-0321 to the extent inconsistent with the amendatory language added to subsections (c) and (d). […] (l) Each participating utility shall be deemed to have been in full compliance with all requirements of subsection (b) of this Section, subsection (c) of this Section, Section 16-108.6 of this Act, and all Commission orders entered pursuant to Sections 16-108.5 and 16-108.6 of this Act, up to and including May 22, 2013 (the effective date of Public Act 98-15). The Commission shall not undertake any investigation of such compliance and no penalty shall be assessed or adverse action taken against a participating utility for noncompliance with Commission orders associated with subsection (b) of this Section, subsection (c) of this Section, and Section 16-108.6 of this Act prior to such date. Each participating utility other than a combination utility shall be permitted, without penalty, a period of 12 months after such effective date to take actions required to ensure its infrastructure investment program is in compliance with subsection (b) of this Section and with Section 16-108.6 of this Act.”

15. Commonwealth Edison Press Release, “ComEd, Illinois Business Owners Testify About Economic Benefits of Grid Modernization,” April 6, 2011.

16. Abraham Scarr and Jeff Orcutt, “Guaranteed Profits, Broken Promises,” December, 2020, Chapter 2.

17. See ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing 18 – 35, for commentary.

18. Illinois Compiled Statutes, 220 ILCS 5/16-108.5(c)&(d). For example, see ICC Docket No. 19-0387, Final Order, Appendix A (“forward look” filing year) and Appendix B (“backward look” reconciliation year).

19. ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, 18.

20. ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, 36.

21. ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, 26. The Order on Rehearing calls the Rate of Return the Weighted Average Cost of Capital. These are one and the same.

22. ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, 23-25.

23. ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, 18-20.

24. ICC Docket No. 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, 24.

25. ICC Docket 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, pages 17,18.

26. ICC Docket 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, pages 2-5.

27. ICC Docket 11-0721, Final Order on Rehearing, pages 15, 17.

28. Calculated from each respective year’s formula compliance filing (ICC Docket Nos. 11-0721, 12-0321, 13-0318, 14-0312, 15-0287, 16-0259, 17-0196, 18-0808, 19-0387, and 20-0393), which is revised and populated in accordance with the respective Orders to determine the annual net revenue requirement and then submitted to the ICC as a compliance filing on e-Docket under the respective docket number as Exhibit B. The reconciliation calculation uses page 6 (line 29 – Variance with Interest minus line 1e Variance with Collar); the pension calculation uses Pension Funding Cost found on page 12; the rate base reconciliation averages the previous year’s year-end reconciliation rate base with the current year’s and updates the calculations on page three to get the difference and does not add any interest to the reconciliation because the impact of interest is considered in the impact of the reconciliation Interest calculation

Topics

Authors

Abe Scarr

State Director, Illinois PIRG; Energy and Utilities Program Director, PIRG

Abe Scarr is the director of Illinois PIRG and is the PIRG Energy and Utilities Program Director. He is a lead advocate in the Illinois Capitol and in the media for stronger consumer protections, utility accountability, and good government. In 2017, Abe led a coalition to pass legislation to implement automatic voter registration in Illinois, winning unanimous support in the Illinois General Assembly for the bill. He has co-authored multiple in-depth reports on Illinois utility policy and leads coalition campaigns to reform the Peoples Gas pipe replacement program. As PIRG's Energy and Utilities Program Director, Abe supports PIRG energy and utility campaigns across the country and leads the national Gas Stoves coalition. He also serves as a board member for the Consumer Federation of America. Abe lives in Chicago, where he enjoys biking, cooking and tending his garden.

Find Out More

Illinois PIRG 2024 Legislative Agenda

Dry cleaner with an electric clothes dryer

Need to replace your water heater? Consider electric