Closing The Billion Dollar Loophole

How States Are Reclaiming Revenue Lost to Offshore Tax Havens

New report tells how some states have found a simple reform to reclaim significant revenue lost to offshore tax havens. Includes estimates of how much each state loses in state revenue to offshore tax haven abuse and how much each state would gain by closing the "water's edge" loophole.

Executive Summary

Every year, corporations use complicated gimmicks to shift U.S. earnings to subsidiaries in offshore tax havens – countries with minimal or no taxes – in order to reduce their state and federal income tax liability by billions of dollars. Tax haven abusers benefit from America’s markets, public infrastructure, educated workforce, security and rule of law – all supported in one way or another by tax dollars. But they use tax havens to escape supporting these public structures and benefits. Ultimately, ordinary taxpayers end up picking up the tab, either in the form of higher taxes or cuts to public spending priorities.

While much attention is paid to the impact of tax haven abuse on federal revenue, offshore tax havens also reduce state revenue because state tax codes are often tethered to federally defined taxable income. With Congress often gridlocked, states should take action to reduce the impact of offshore tax havens on state budgets.

Montana and Oregon have passed laws to curb offshore tax haven abuse and collect tax revenue that otherwise would be lost. These two states simply treat a proportionate share of the income that corporations book to known tax havens as domestic income for state tax purposes, since it can be reasonably extrapolated that the income arose from business activity in those states.

Other states can also collect some of the revenue lost to offshore tax havens by adopting policies similar to those in Montana and Oregon. Specifically, states must:

- Close the “water’s edge” loophole by mandating that companies include their U.S. profits held in offshore tax havens when calculating taxes. In many states, companies calculate their tax liability based on their income held in subsidiaries incorporated within the water’s edge (that is, within the United States). By declaring a statutory list of tax havens, states can tax corporate profits held in tax havens that lie past the water’s edge.

- Before closing the water’s edge loophole, states must adopt “combined reporting,” which requires corporations to list the profits of all their subsidiaries on their tax forms. Combined reporting provides states with a ready formula that can be applied to tax haven income to determine which portion should be taxable by the state.

To date, 23 states and the District of Columbia have adopted combined reporting requirements, but of these jurisdictions only Montana and Oregon have also closed the water’s edge loophole by creating a statutory list of tax haven countries to be accounted for in corporate combined reports. Montana is now collecting millions of dollars in additional tax revenue and Oregon is poised to do the same with its new law coming into force in 2014.

- Closing the water’s edge loophole allowed Montana to collect $4.2 million in corporate taxes that would have otherwise gone uncollected in 2008. In 2010, the last year for which data are available, closing the water’s edge loophole allowed Montana to collect an additional $7.2 million.

- After closing the water’s edge loophole in 2013, Oregon’s Legislative Revenue Office expects the state will collect $18 million in corporate taxes in the 2014 tax year that would have otherwise gone uncollected. In the 2015-2017 biennium, the Legislative Revenue Office expects the state will collect an additional $42 million.

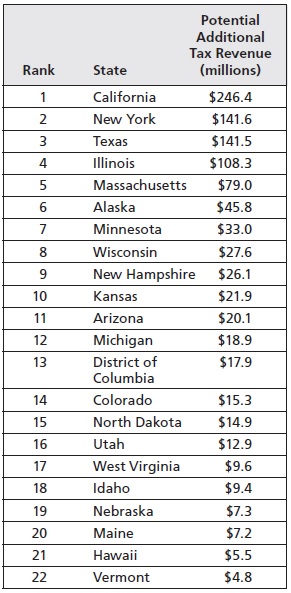

Other states too should close the water’s edge loophole. In doing so they could collect millions in additional tax revenue to reduce the tax burden on other taxpayers or increase needed services. In addition to Montana and Oregon, twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have combined reporting and could implement this reform. If they had joined Montana and Oregon in closing the water’s edge loophole, they could have collected an additional billion dollars in combined revenues in 2012 (note that this figure was calculated using 2012 data for all states except Massachusetts where an official, state-generated estimate for 2011 was used instead) (see Table ES-1).

Table ES-1. Closing the Water’s Edge Loophole Would Have Generated Millions of Dollars of Additional Tax Revenue in 2012*

* With one exception – Massachusetts – all revenue estimates in this table are for 2012, calculated using 2012 data. The Massachusetts figure represents the midpoint of an officially calculated range produced by the Massachusetts Department of Revenue using 2011 data. The 2012 figure calculated using our own conservative methodology ($62.1 million) aligns closely with the low end of the officially calculated range for 2011 ($64-$94 million). See note 45 for more information.

Closing the water’s edge loophole would be a good start for states in reclaiming a portion of the state revenues lost to tax havens. In 2011, offshore tax havens cost states an estimated total of $20.7 billion in corporate tax revenue. California lost $3.3 billion to offshore tax havens – the most lost by any state. States that close the water’s edge loophole could also put pressure on Congress to stop offshore tax haven abuse at the federal level.